Introduction

In recent times, there is a worldwide shift of attitude taking place within organizations; from a short-term approach driven predominantly by creating value for shareholders to a long-term value creation model where shareholders become one of the many stakeholders for the company to consider when creating value, and where social and environmental considerations play an important role[1].

- What does this mind shift mean for organization’s innovation approach and what’s the role of Intellectual Property (IP) in this transition?

- Is it a logical step to also share the related IP freely in order to accelerate the diffusion of relevant IP[2]?

- Or is the more classical approach still valid; guard and protect your IP closely as an ongoing boost for your business model?

- A key question is: what is the best way to use IP to create social impact?

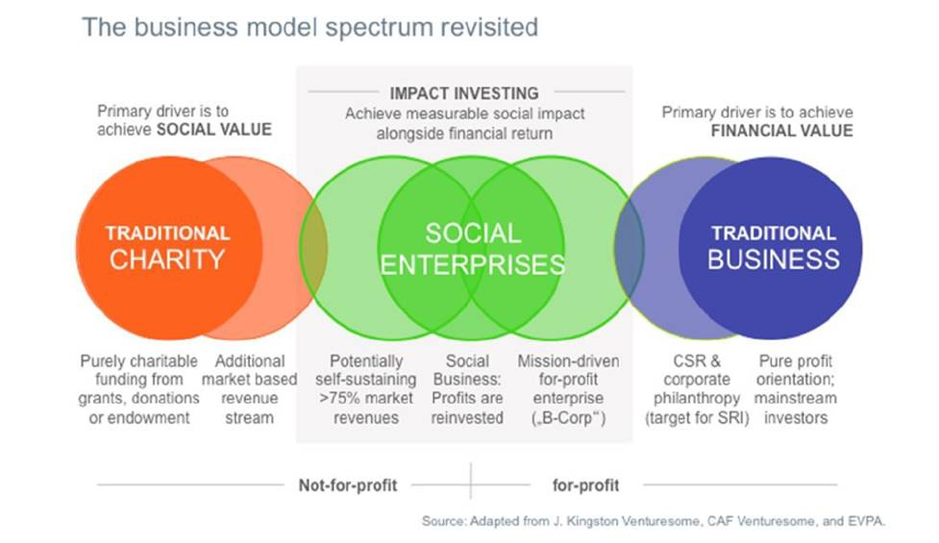

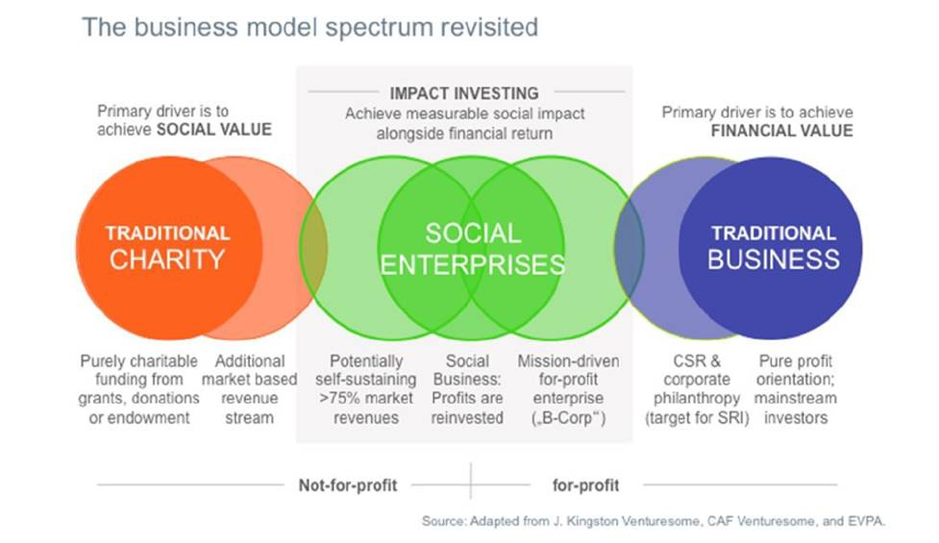

Today, organizations manoeuvre themselves in a range of positions from a traditional charity to a traditional business. On the one hand a traditional business needs to adapt to the changing demands of the society that is calling for more responsible action from business. Commercial organizations are prioritizing the creation of a ‘shared value’[3] within or from their traditional ‘for profit’ business, in multiple ways: creating impact by fulfilling their Corporate Social Responsibilities (CSR) obligations, innovation for social impact within their core business itself, supporting social innovators with technology transfer or capacity building, taking up projects that aim to fulfil the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG’s), etc. On the other hand, traditional charities, have to sustain themselves to continue the work they do for communities in the most relevant way.

Whether an organization is a business or a charity, or somewhat of a hybrid, they face similar challenges: creating value and capturing value.

Questions lots of organizations nowadays struggle with are the following:

- How can you capture the value you’ve created – in your new ideas, knowledge, Intellectual Property (IP) – in social innovation, whether it’s for profit or not?

- Do ‘not for profits’ and ‘for profits’ take a different approach to social innovation?

- Does social innovation mean revealing ideas, knowledge and IP for free?

- Are there bigger factors that influence how we deal with IP in social innovation?

- How does this impact a business model for a company or a sustenance model for a charity?

- What do organizations aiming for solutions through social innovation and shared value choose; open or closed innovation strategies?

At the initiative of Ms Raluca Radu, Legal Director of Fairphone, a panel discussion on ‘Developing Sustainability through Intellectual Property’, took place at the IP World Summit in Amsterdam, end of October 2019, attempting to address some of these questions. We had an engaging discussion and exchanged insights from different perspectives (industry, academia and the civil society).

Raluca asked me to introduce ‘the Innovation Matrix’ and we discussed how it can be used to create strategies designed for social innovation. In this blog I will summarize some aspects that I believe may influence the approach for social innovation and some examples as discussed in the panel.

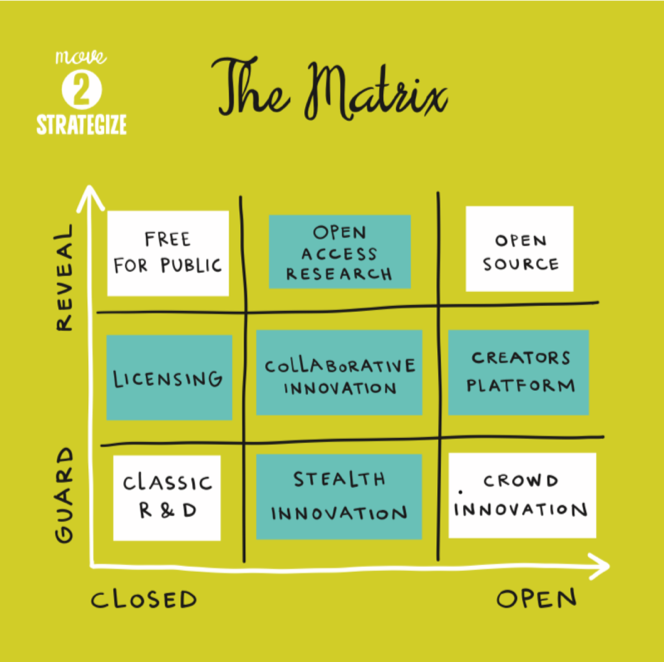

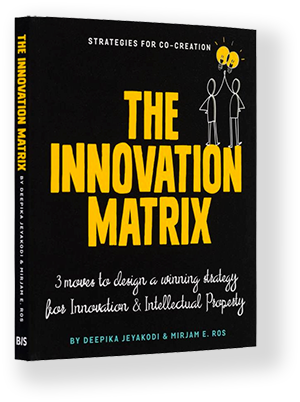

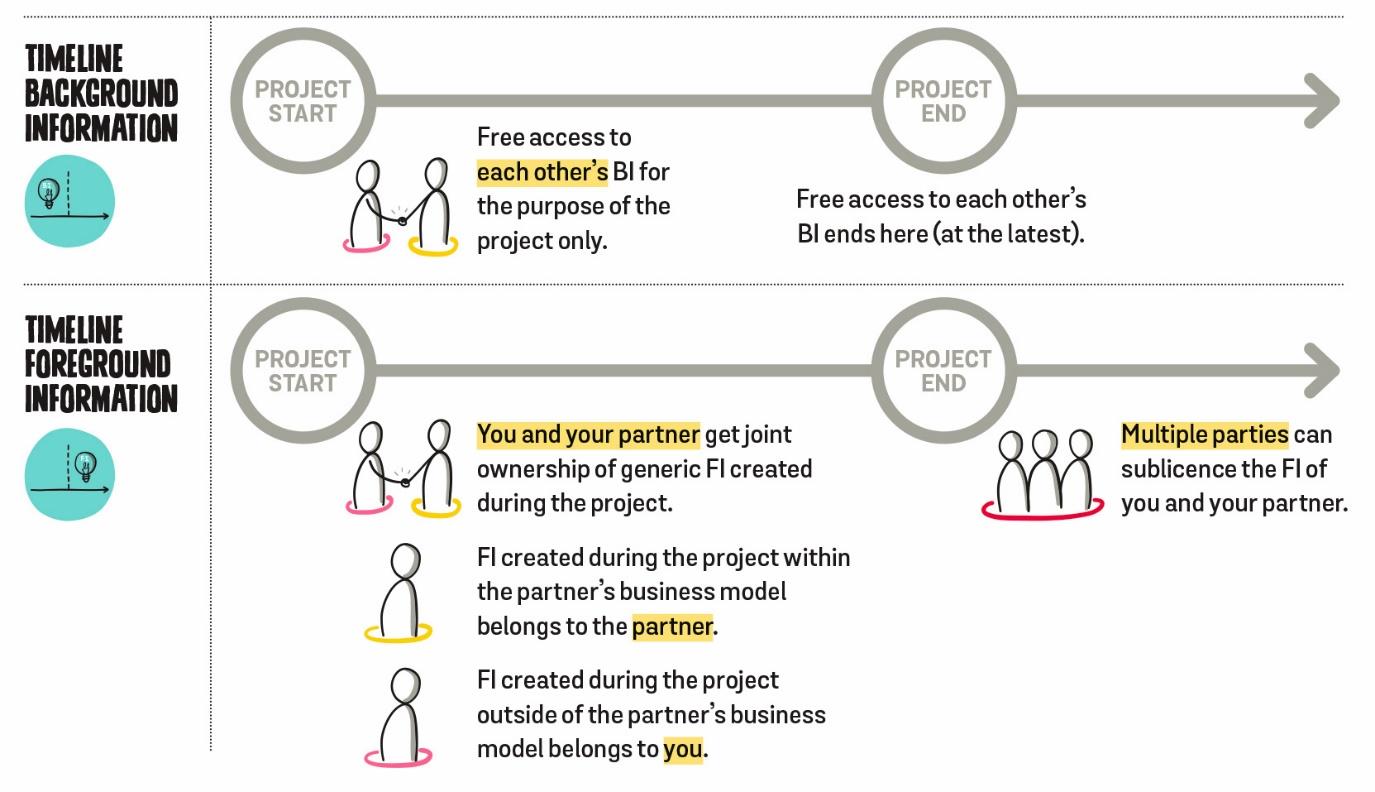

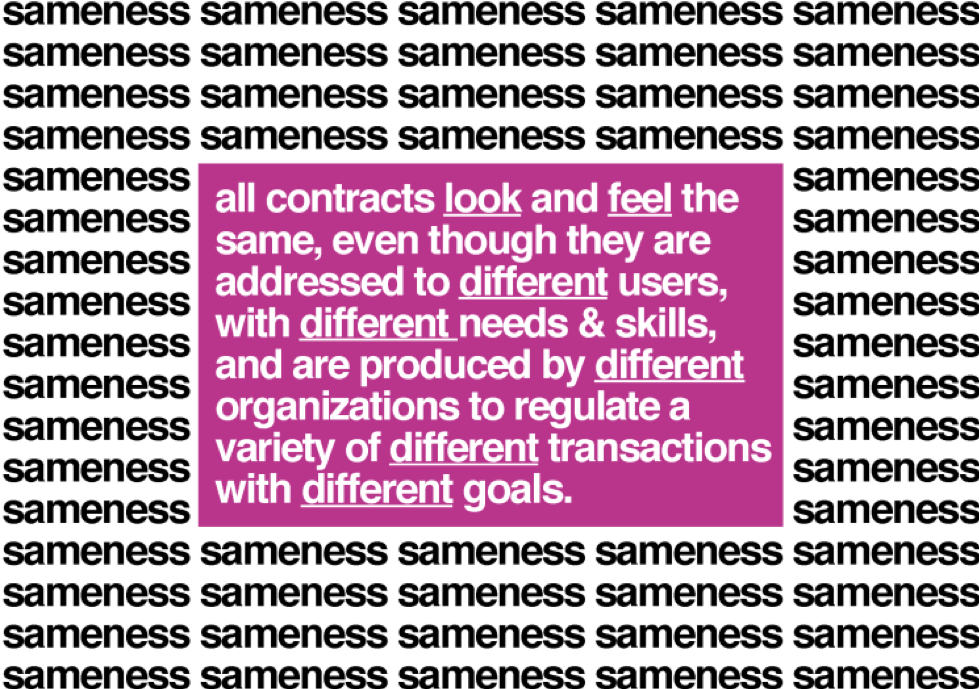

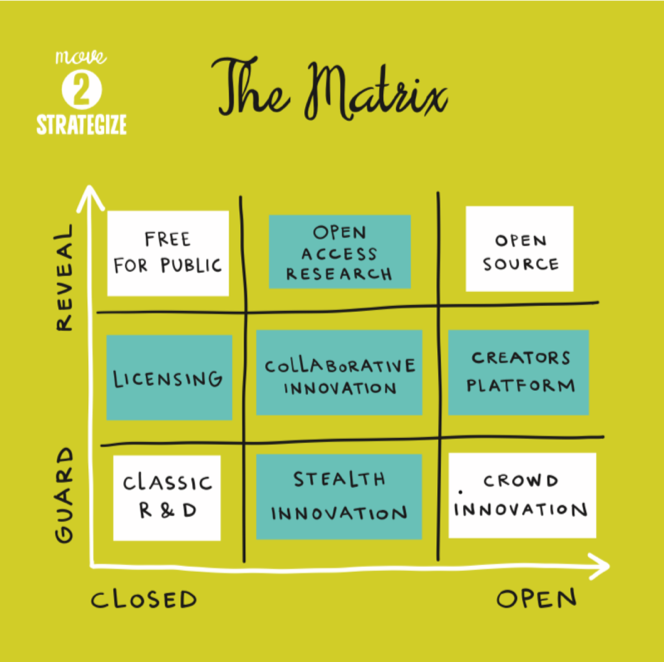

The Matrix gives an overview of nine possible innovation & IP strategies. The x-axis of the Matrix represents how many parties you can work with: open versus closed innovation, so whether you innovate individually, with some parties, or with many parties. The y-axis represents the approach taken towards IP: whether the organization guards their IP, licenses it to some or instead reveals it to many. The four corners of the Matrix are the extremes with Classical R&D, Reveal to the Public, Open Source and Crowd Innovation. The cross or the mellow middle as we call it is dynamic in the sense that organizations can get creative in their approach to Innovation and IP. For a more detailed explanation including many real life examples, please refer to our book ‘The Innovation Matrix, 3 moves to design a winning strategy for Innovation & Intellectual Property’, BIS Publishers, Amsterdam, 2019.

I presented three key questions surrounding social innovation and IP:

- Which IP is core for your organization in order to create social impact?

- Can you better guard or reveal your IP?

- Can diffusing your IP stimulate social impact and/or the business model?

In the cases presented and discussed at the panel you can get new insights into the strategy devised by raising these questions.

For example:

- G-STAR – international fashion brand – is a nice case to illustrate the relevance of the core/non-core question. They made the process of producing sustainable denim open source. The production process of the jeans fabric as raw material is not considered as their core they want to compete with. Their core is the design and branding of their jeans. So they used their non-core IP in order to make their industry more sustainable.

- ColorADD – a colour identification system to help the colourblind – uses two diffusion strategies: one is licensing for free for use of their code in the educational field, and two, the sale of the code through paid licenses in all other fields of use.

- Tesla – global electrical car manufacturer – is a good example of a company diffusing their IP to create social impact while also boosting their business model. They opened up their IP portfolio for parties using it for the good and to stimulate the whole industry to quickly develop and grow. In fact the classical car industry was the real competitor for all.

These cases illustrate that you can diffuse your IP and at the same time protect them. It’s not a definite ‘or-or’, often it is ‘and-and’. You can guard your IP with paid licensing in one market and in another market reveal your IP for free.

To stimulate the debate I summarized and concluded that if you are a business engaged in social innovation:

- First assess which IP is core and non-core for your business. Only diffuse your core IP for free when it is a catalyst for your business model.

- If you are diffusing your core IP for free and it adds as a catalyst for social innovation only and not for your business model, then it could lead to the end of your companies’ life cycle.

- If you purely aim for social impact and you have your investors who are backing you in this ‘diffusion for free’ strategy of your core IP, it could still be the right thing to do.

The same principles can be applied to not for profits, if your replace the term business model with your organization’s sustainability model.

The panelists challenged some of these propositions by discussing the scale between social value and financial value, both for ‘for profits’ and ‘not for profits’. Ref the visual below[4].

The approach taken by social innovators with business ambitions can be largely different from that of non-profit NGOs. Further, the separation of business model from responsible business conduct was discussed. Sometimes, the core business can be driven by the demands of ‘conscious customers/users’, in which case, the social objective may trump the business model in order of priority. Even so, I believe that a non-profit, expending its limited resources in addressing a social issue, must pay further attention to how it diffuses its IP. Their IP too can be managed otherwise – without making it free in all cases – while creating the social impact they desire.

One of the outcomes of our research is that the most successful organizations often combine two or three strategy boxes from the Matrix instead of just applying one strategy. The success lies in the combination, based on the needs and objectives of the organization. The context within which an organization makes these choices can be analysed quickly in a structured manner by using the following six ‘Building Blocks’: interests, contributions, technology, business model, industry, and organization (‘Move 1’ in our book ‘the Innovation Matrix’).

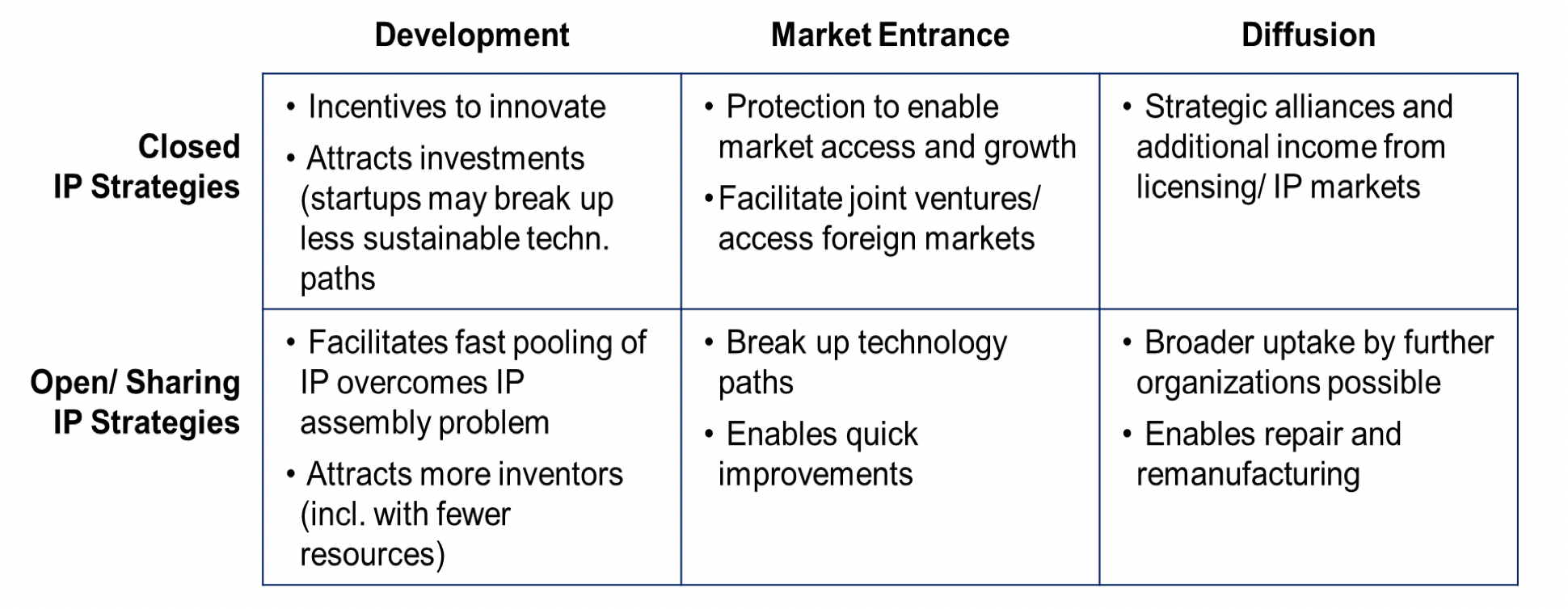

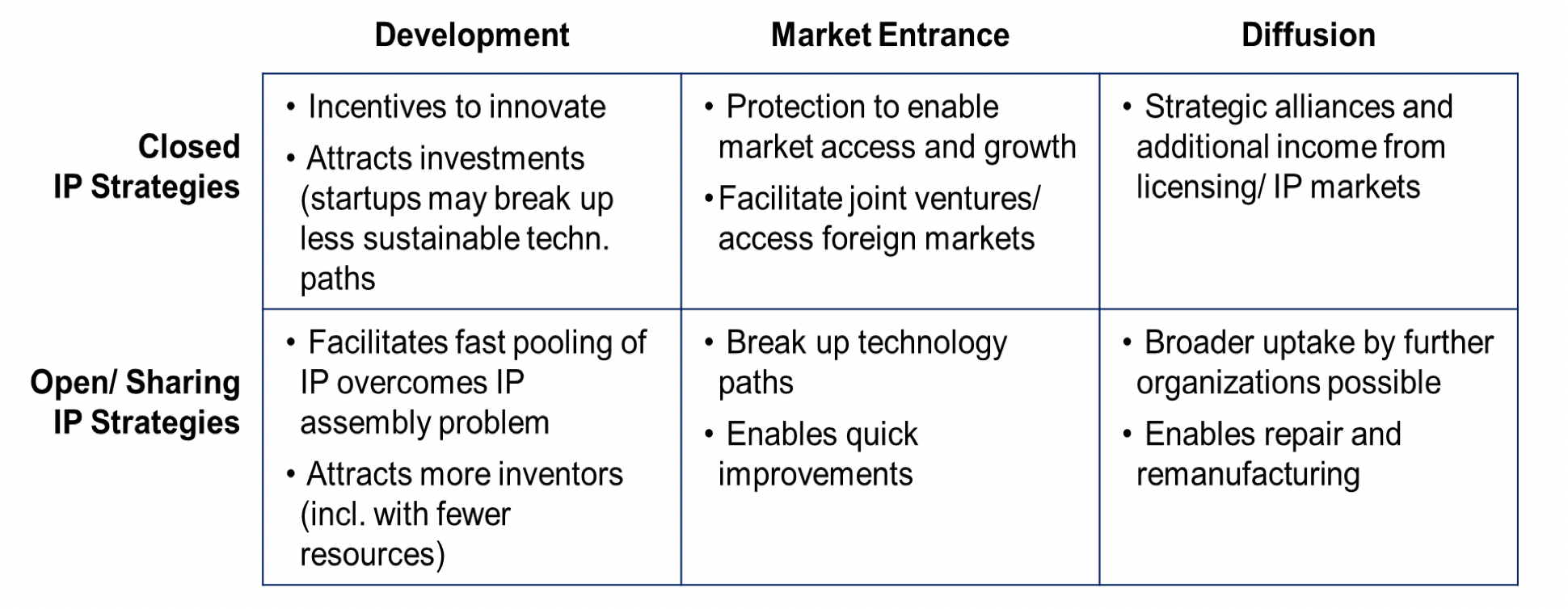

Literature on Innovation & IP strategy in general and especially on IP strategies in social innovation is still scarce. I was very happy to learn that Professor Elisabeth Eppinger, from the University of Applied Science in Berlin, started some important and interesting research projects in this field. She shared the below overview of benefits of both open/sharing and closed IP strategies for sustainable innovations.

One of the interesting aspects Elisabeth referred to is that open/sharing IP strategies can enable repair and remanufacturing, which could be quite beneficial to lengthen life cycles of electronic articles. While companies that serve a global market have little incentives to install repair and remanufacturing services for their products, IP such as trade secrets and patents in some instances block others to set up repair centers. Opening IP, e.g. with a differentiated licensing approach to support consumers and repair and remanufacturing companies may help achieving the environmental agendas set by the UN and many nation states.

This is one of the strategies used by Fairphone. Fairphone aims to maintain their phones for a period of 2 to 5 years. One of Fairphone’s manifesto’s is “if you cannot repair it, you don’t own it”. The design of their smart phone is modular and the phone can quite easily be repaired, having received a score of 10/10 from iFixit. iFixit company sells repair spare parts for electronics and publishes free online repair guides on its website. Fairphone provides hardware and software maintenance for this extended period, as part of their regular commercial servicing.

Elisabeth further underlined the importance of embracing IP as a tool to facilitate Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and sustainability aspects in the overall business strategy. While it is challenging to align the IP strategy with the business model, IP can serve as a tool, e.g. through differentiated licensing approaches, to foster new forms of collaboration for innovation and market diffusion.

Andreas Iwerbäck, Director of Group IP Intelligence at Husqvarna, based in Sweden, observed that the Innovation Matrix is dynamic by nature. Husqvarna is transforming from a hardware company (outdoor power tools) with a more classical R&D approach in the past, to a hardware and software company which is embracing sustainable innovation. The proof-of-concept “Battery Box” (community demand driven app – online tool shed) and the GARDENA smart system (garden maintenance app accessible to compatible devices from other manufacturers as well, which can be connected to the system via the app), both take a platform approach to engage their customers.

Sarah Norkor Anku, Senior Partner of Anku at Law from Ghana, shared some examples of innovation that have created a social impact in the African continent:

- i-Cow a mobile app built around an agricultural ecosystem for small-scale dairy farmers in Kenya prompts farmers on vital days of cows gestation period; helps farmers find the nearest vet and AI providers; collects and stores farmer milk and breeding records and sends farmers best dairy practices[5].

- Leti Arts (video game company) from Ghana, whose mission is to find a place for African created content in the global community, diffuses their technology through MTN (telecom) to have outreach. They use MTN’s resources and market space to diffuse its technologies, and more importantly achieve their cultural objective.

Further, she highlighted the importance of a sustainable supply chain and the use of superior technology which can help address certain environmental crises, as has occurred in the mining sector in Ghana. Particular to Artisanal and Small Scale Mining (ASM) of which 85% is illegal in Ghana. These miners use rudimentary and inferior technologies. With the diffusion of superior sustainable technologies, the adverse effect on the environment will be minimized.

Raluca added that the immediate question here is: who should demand for, pay and provide for improving the environmental output and the health and safety of the ASM miners? Is it the governments, the ASM miners themselves, the local companies who buy from the ASM miners and then sell their products to companies that operate in the international markets, is it the international companies that buy from the local companies, or maybe the ultimate consumers? This is probably one of the biggest debates that are going on in our societies now, both at a regulatory and political level. We do see a trend of emerging legislation across Europe that is aiming to ask companies to do more due diligence of their supply chains, which is driven by the EU corporate sustainability agenda[6].

Discussions over this topic have kept me thinking in the past months because of the many influences over and dynamics at play in social innovation. As panelists, we came out with many more ideas and questions on this topic. To feed our minds and build on this topic, we invite you to share your experiences with us. Interesting subjects we would like to further explore are the following:

- What drives the customers and users of social and sustainable organizations? What is the role of conscious customers/users in social innovation?

- What is the role of policy makers, regulators and law makers in social innovation? How can governments stimulate social innovation?

- A question was raised about stealth innovation; what is it, why would a social company use it and how does it influence IP strategies?

- How does social innovation and measuring its impact influence corporate governance? What needs to be updated here; which key performance metrics and incentives are needed and wished?

If you would like to know more or if you would like to participate in our research and discussions on this topical subject, please contact one of us.

________________

[1] https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/19/business/business-roundtable-ceos-corporations.html

[2] Eppinger, E., N. Bocken, C. Dreher, A. Gurtoo, R. H. Chea, S. Karpakal, V. Prifti, F. Tietze, and P. Vimalnath. The Role of Intellectual Property Rights in Sustainable Business Models: Mapping IP Strategies in Circular Economy Business Models. Presented at the 4th International Conference on New Business Models, Berlin on 1-3 July 2019

[3] Defined as policies and operating practices that enhance the competitiveness of a company while simultaneously advancing the economic and social conditions in the communities in which it operates, in the Harvard Business Review: ‘Creating Shared Value’ by Michael E. PorterMark R. Kramer, from the January–February 2011 Issue.

[4] Source: Adapted from J.Kingston Venturesome, CAF Venturesome, and European Venture Philantropy Association (2015) https://www.sosense.org/the-finance-paradoxon-for-social-enterprises/

[5] http://icow.co.ke/about

[6] http://corporatejustice.org/news/16793-mandatory-human-rights-due-diligence-an-issue-whose-time-has-come

Mirjam Ros, author of ‘The Innovation Matrix, BIS Publishers, Amsterdam, 2019 together with Deepika Jeyakodi

Panel leader:

- Raluca Radu, Legal Director Fairphone

Panel members:

- Elisabeth Eppinger, Professor at the University of Applied Science in Berlin

- Sarah Norkor Anku, Senior Partner of Anku at Law from Ghana

- Andreas Iwerbäck, Director of Group IP Intelligence at Husqvarna

Read More